Signals that Gather

By Tom Wachunas

EXHIBIT:

Signals that Gather, abstract paintings

by Jack McWhorter, Bridget O’Donnell, George Schroeder, and Nancy Seibert, at

The Painting Center, 547 West 27

th Street, New York, New York (212) 343-1060

www.thepaintingcenter.org THROUGH FEB. 27, 2016

[Note to ARTWACH readers: I have written

about all of the artists here in the past as they have exhibited locally,

including shows at Main Hall Gallery on the campus of Kent State University at

Stark. I felt honored when Jack McWhorter asked me to write the essay for this

New York City show’s digital catalog, and so here I offer it for your reading

pleasure. The exhibit opened in New York on Feb. 4.]

According to the Roman author Pliny the Elder,

the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis once competed against fellow artist Parrhasius

to see who could make the most realistic image. Zeuxis painted a bunch of grapes so

convincingly that birds attempted to eat them. But when he tried to remove the

disheveled curtain he thought was covering his rival’s work, he discovered that

the curtain was in fact a painting, thus assuring Parrhasius the victory.

In many ways this

legend from the 5th century BCE encapsulates the raison d’etre behind Western painting

that would hold court for roughly the next two millennia: the idealized

imitation of the visible world. Painters were expected to be prestidigitators –

master illusionists who fabricated beautiful windows on physical reality. Call

it an intellectual slavery to the apparent.

Fast forward to Modernism’s

insistence on the flatness of the picture plane as a discrete object in itself,

and then further into the pluralistic explorations of concepts and materiality

commonly referred to as “Postmodernism.” It is a pesky term at best. Suffice to

say that when we strip away the often arcane, sometimes silly philosophical

rhetoric that surrounds it, we’re still left with the realization that the

essential focus of Postmodernism is, arguably…Modernism. More precisely, it’s

an ongoing commentary on, and re-assessment of, Modernist ideologies.

That said, the

four artists exhibited here – George Schroeder, Nancy Seibert, Bridget

O’Donnell, and Jack McWhorter – represent three generations of combined

experience in examining the legacy of Modern/Postmodern abstraction. Each has

developed a distinctive visual language - a codified system of interrelated

markings, shapes, colors and planes that can simultaneously appear to congeal

and disperse along the image surface. The painters’ manipulations of these

signs, or signals, along with their respective palettes, may refer to “real

world” sources, but only in a peripheral or idiosyncratic way. And even as these painters have developed

effective means by which to imply elements such as motion, rhythm, or tension,

they do so without delineating specific

narratives or subjects.

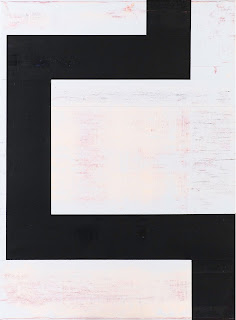

While the apparent

structural rigidity and high contrasts of dark and light hues in George

Schroeder’s paintings might suggest a kinship to Minimalist aesthetics, it is

their quietly regulated surfaces that imbue them with a palpable sense of

intuitive expressivity. Schroeder’s paint application allows for delightfully

integrated passages wherein the top skin of color has been uniformly scraped

away to reveal the grainy tactility of the canvas, tinted earlier in the

painting process with shadows of underlying color

.

Amid

the precision of flat, hard-edged geometric design there is also a playful

spatial dynamic – a gentle fluctuation between positive and negative planes

that in turn balances rhythmic movement with stillness. What finally emerges

from these works is a lyrical architecture of sorts, heraldic in its

simplicity, and exquisitely engineered to generate moments of sublime

equilibrium.

Nancy Seibert has

drawn her pictorial inspiration from nature in what she calls “…a synergy of

paint and energy produced in brushstrokes…” Her recent mixed media works are

highly tactile, atmospheric visions that can suggest the volatile movement of

wind, water, or perhaps foggy mists across earthen tracts. Indeed, her recent

canvases look as if pigments and particulate matter, once deposited on the

surface, are in the process of being swept away, leaving in their wake vast

white voids. Or perhaps the reverse is true – materials are in the process of

arriving to fill empty space.

In any case, the

figure-ground shifts are intriguing. Seibert’s technique is spontaneous enough

to allow her to frame essences, imbuing her surfaces with a sense of transient

physicality. These are translations of, or meditations on, changeabilty. And you

can almost hear the energetic motion of mark-making. Loud silence, or silent

noise?

A related spirit of

flux and ambiguity is clearly at work in the mixed media works on paper by

Bridget O’Donnell. Her pieces, however, are more autobiographical than

ostensibly “natural.” Sourced in maps of places where she has lived, you might

consider her visions collectively as an abstract journal of sorts, describing

not just the rhythmic patterns of street layouts, but moving or “writing”

through them in variable states of mind and heart.

There is a tangible

sense of urgency, mystery, and maybe even madness in her passages of scribbles,

doodles, and amorphous clouds of pigment interspersed and synthesized with the

grid configurations. It’s as if she wanted to quickly record memories or sensations

before they disappear into the ghostly backgrounds and disintegrate completely.

Fragments float, are retrieved, or slip away, in a frenetic and dramatically

engaging simultaneity of construction and disruption.

Jack McWhorter is

a painter’s painter. He’s a masterful colorist who revels in the materiality of

oil paint, the physicality of the brushed mark or shape, the gestural fluidity

of line. “I am drawn to organisms found in nature,” he recently stated, “and

respond to their power as factual beginnings in making paintings, in the same

way that a landscape painter might use the landscape as a factual beginning.”

But only the

beginning. In exploring the confluence of art and nature, or science, McWhorter

formalizes his intuition in these current works via a continued focus on

hybridization and what he calls morphology -

“…shapes and forms indicating states of growth or becoming…” His

compelling visual syntax is rigorously grounded in the push-pull dynamic between

organic/ geometric shapes, spectacular chromatic relationships, and spatial

anomolies that might incidentally evoke natural objects or phenomena, yet

effectively transcend literal illustration. In their interactions of rhythm,

pattern and motion, these paintings pulse and crackle with a jubilant energy,

describing structures or processes at once matured and nascent, static and

changing.

McWhorter’s

invigorating offerings, and for that matter those of the other artists he has

gathered here, take me back, oddly enough, to Zeuxis and Parrhasius. They

embodied a painting tradition that never outgrew meticulous narrating of the visible world.

I’m reminded that one difference between representational and abstract painting

is the difference between prose and poetry.

The stylistic

variances among the works in this exhibit notwithstanding, each artist

demonstrates a unique fluency in some dialect of abstraction. It is a poetic

language to be sure, and one that can be admittedly complex, even confounding. But

it remains ever true to its purpose of embracing that which is most ephemeral

and ineffable about not just making art, but I dare say being alive.

PHOTOS, from top: Sketch, acrylic on linen, by George

Schroeder; Shore Dreams II, mixed

media by Nancy Siebert; Akron, mixed

media by Bridget O’Donnell; Slow

Formation, oil on canvas by Jack McWhorter