Reading Beneath,

Behind, and Between

|

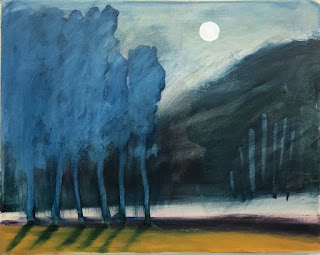

| Ursa Minor, Facing North / Jack McWhorter |

|

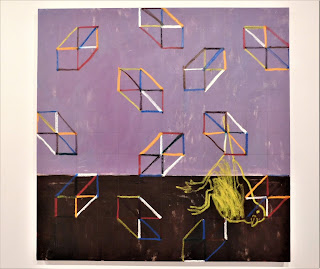

| Lunch with Picasso / Patricia Zinsmeister Parker |

|

| Partially Buried 3 / Earl Iselin |

By Tom Wachunas

EXHIBIT: JACK

MCWHORTER: VISIBLE UNIVERSE / PATRICIA ZINSMEISTER PARKER: LUNCH WITH PICASSO /

EARL ISELIN: STACKED

November 4 – 27, 2021

/ The Painting Center, 547 West 27th Street, Suite 500, New York, NY

10001, (212) 343-1060

https://www.thepaintingcenter.org/

I was especially honored to write the

catalogue essay for this exhibit.

Here’s a link for seeing artists bios and their exhibited

works:

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e51549cd0f681f932c3e9c/t/617cad918fac1d3a0d07cf2b/1635560852805/McWhorter_Parker_Iselin_Catalogue+2021.pdf

“If good art illustrates anything at all, it’s likely to

be a story you didn’t even know needed telling.” - David Salle

In the

introduction to his 2016 book, How to See, painter and critic David

Salle wrote, “Art is more than a sum of cultural signs: It is a language both

direct and associative, and has a grammar and syntax like any other human

communication.”

This analogy, while

complex and expandable, is useful in “reading” contemporary painting. Think,

then, of the three painters in this exhibit – Jack McWhorter, Patricia

Zinsmeister Parker, and Earl Iselin - as writing in dialects. Each of their

respective dialects is in its way a discreet synchronicity, or a dialogue,

transpiring in unique terrains wherein the painter straddles the fluctuating

boundaries between representation and abstraction.

In the past, Jack

McWcWhorter has characterized his process and product as “personal

archaeology.” For this group of recent paintings on paper, that description

remains potently apropos. Equally potent is the wide arc of his subject matter,

born from his question, “How can one give form to one’s connection with the cosmos

whether it be lost or hidden?” He adds this consideration: “Contemporary

cosmology challenges us to look at nature in new ways and to see the inorganic

world from broad areas; art, astronomy, chemistry, earth sciences and physics.”

At the core of his aesthetic

is a persistent navigation of tensions and harmonies within symbiotic

dualities. His compositions, which he calls “live surfaces,” are clusters or

matrixes of lines, shapes, and patterns that juxtapose accumulations and

singularities, gatherings and dispersals. Like an explorer’s field notes on

remembered sights and sites, places and spaces, his pictures often entwine a

then with a now, as if remembering their own beginnings even as they are

transformed by his imagination into new visual moments.

Live surfaces to

be sure, they’re drawn with a vigorous, gestural immediacy, combining marks

made in broad and loose ways with more concentrated movements of the hand that

we might associate with calligraphy.

Additionally,

McWhorter’s exuberant palette imbues his imagery with a numinous energy,

bringing to their spatial dimensionality a sensation of rhythmic pulsing.

Rising from evanesced fields of personal history and the memories held there,

his transfixing configurations have a heartbeat.

Similarly, visceral

gesture, remarkable chromatic dynamics, and personal history are prominent in

Patricia Zinsmeister Parker’s works. Recently she wrote “I have always believed

that abstract art and representational art are one and the same. It’s just a matter

of scale and particularity.” Her pictures are invigorating records of

spontaneous actions – an immersion in the primacy of painterly impulse and

intuition.

In a spirit of

equanimity, Parker presents her canvases here in pairs, suggesting a continuum,

or conversation, between a non-objective work and one of a relatively more

representational nature. For example, Girl in White Tutu sits beside My Leaky

Fawcet, while Wallflower attends Lunch With Picasso. Two pictures reading as a

single entity, these pairings are unified by one or more formal commonalities,

such as a recurring color, shape, or pattern motif.

There was a period

in Parker’s career when she deliberately painted with her “untrained” left

hand. Consequently, the representational elements in her works regularly

possessed a distinctive awkwardness. She has recently commented that her

leftist approach, if you will, is a thing of the past. Her current paintings

signal a re-emergence of her trained right hand - what she calls her “… return

to figurative work and draughtsmanship skills - those skills being undermined

and buried for decades by the use of my left hand.”

Parker’s drawing

acuity is especially evident in her renderings of female forms. They seem to

emerge from under surrounding scruffy veils or rough layers of paint in a

fluid, even graceful manner, deftly capturing the subtlest of bodily attitudes.

Insightful and

inciteful, Parker makes art that wags a sassy finger in your face and rattles

your sense of “finished” aesthetic decorum. As the sardonic titles of her

paintings suggest, such as Caught in the Act of Painting, she’s a painter

seriously engaged in mindful play, and generous enough to provide us refreshing

cause to chuckle.

Meanwhile, for Earl

Iselin, the act of painting is in many ways an ongoing inquiry into the very

motives and meanings of creativity. Metaphor is certainly an active force in

his iconography. “In five of the paintings I have offered,” he writes, “I’ve

used isometric perspective, which has the penchant to lift, in essence to ‘sky’

the painting, as if to give flight to imagination.”

Those five

paintings share a title, Partially Buried, named after Robert Smithson’s 1970

land art installation, Partially Buried Woodshed. Made on the grounds of Ohio’s

Kent State University when Iselin was living there, it was a site he visited,

occasionally sitting inside, and which he remembers as greatly obscuring his

view of the blue sky, itself a symbol of pure, limitless possibility.

That sensation has

prompted some intriguing philosophizing about history and existence itself.

What he calls ‘skying the painting’ is his way “…of defying the past and

escaping its definition.” Thus his paintings present the shed not as something

dead, collapsed by gravity and entropy, but as a bright-colored geometric

structure, maybe a house, free-floating in an open field dotted with

suggestions of dirt piles or bodies of water.

Meanwhile, his

series of paintings under the collective title of Stack, is a further probing

of history. These smaller individual pieces, some executed in lavishly-hued

impasto, are attached to each other to make large modular grids, evoking a

variety of modernist painting genres such as Color Field, Minimalism,

Expressionism. The Stacks are intended by Iselin to symbolize and encourage

imagination – his, and ours – and to create an energy for really seeing our

present.

And again, Iselin’s

words describe that energy best: “It is…a creative force… to move me beyond the

limitations of my own gravity, beyond myself, that gives purpose to the

painting, a purpose that has everything to do with you. Your sky is as blue as

mine.”

Jack McWhorter.

Patricia Zinsmeister Parker. Earl Iselin. To you, the viewer…enjoy the flight.