|

| Age of Aquariums |

|

| The Blue Egg |

|

| Nanu's Rubaiyat |

|

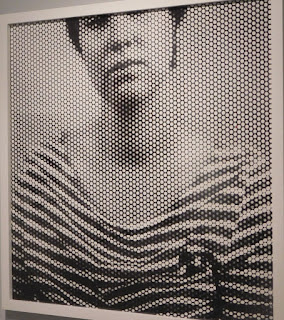

| Girl from Ipanema |

|

| Wood Sprite |

|

| Ginger Jars |

A Liquid Symphony of Luminescence

By Tom Wachunas

“With color one obtains an energy that seems

to stem from witchcraft.” - Henri

Matisse

EXHIBIT: Walk on the

Wild Side - work by Nancy Stewart Matin / at The Little Art Gallery, in the

North Canton Public Library, through

January 20, 2019, / 185 North Main

Street, North Canton, OH / Monday – Thursday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., Friday 10 a.m.

to 6 p.m., Saturday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Sunday 1 p.m. to 5 p.m.

Back in 2011, local

self-taught watercolor wizard Nancy Stewart Matin said in an About magazine article that she was enmeshed enough in art history to think of

painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954) as “…a personal friend.” So it is that even

the title of her retrospective exhibit of 30 paintings spanning about 25 years,

called Walk on the Wild Side, evokes

the temperament of Matisse and some of his Paris cohorts. For a short period of

several years very early in the 20th century, they were known

collectively as les Fauves, French

for “the wild beasts.”

These avant-garde innovators were significant

engineers in advancing a type of abstraction initiated by Post-Impressionist

painters including, among others, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Cezanne. Walking on

the wild side indeed, the Fauves went a step or two farther. In augmenting the

chromatic intensity of paint to unprecedented levels, they boldly liberated

color from the confines of imitating the visible world.

This is not to say

that Matin’s stylized configurations are strictly Fauvist in nature. But to the

extent that her remarkably radiant palette allows arbitrary color to establish its own pictorial space,

independent of merely retinal descriptions of mundane realities, she’s

certainly a kindred spirit.

Her subjects are

diverse – floral, animal, figurative, still-life, and landscape – and

impeccably mounted here by curator Elizabeth Blakemore with all the skill of an

attentive orchestral arranger. This show is a virtual symphony for the eyes,

with the gallery itself becoming a luminous composition, replete with

mesmerizing harmonies, arresting tonal contrasts, and dazzling rhythmic accents

that prance about the room with invigorating energy.

The instruments of

this symphony – Matin’s watercolors – present a world-view, a perceptual

gestalt that straddles the empirical and the magical, the robust and the

delicate, the seen and the felt. Here’s to painting with the soul fully bared,

the eyes wide open, the hand given to childlike abandon.

Childlike, but never childish. Matin is

fully cognizant and in control of her medium’s daunting

tendencies to run too wild, to get too wet, or too muddy.

Her sense of abandon is a judicious one.

An aura of delightfully disciplined ebullience emanates from her work,

springing from a clarity of purpose.

That purpose is as

simple as it is profound – an unabashedly vigorous and joyful embrace of being

alive. Matisse, I think, would approve.